As June progressed, I followed along with James H. Hallas’s comprehensive 2019 Saipan: The battle that doomed Japan in World War II. I found it in the museum shop during the visit we took before I came out here to the National Museum of the War of the Pacific1. The book goes chronologically through the battle. Although I am going to pick up in my broader series about the history of the CNMI and have not gotten to the War yet, there was a particular bit of synchronicity that I would like to note.

This week, I dogsat for friends while they were visiting the mainland. Their house is on the ridge of Mt. Tapochau, the highest point of the island’s spine. I have been taking their pack of four dogs (who have been tolerating Tupu quite well) to the top of the mountain twice a day. There is a small clearing at the summit that marks where, 79 years ago this week, the U.S. Marines crested and held the high ground.

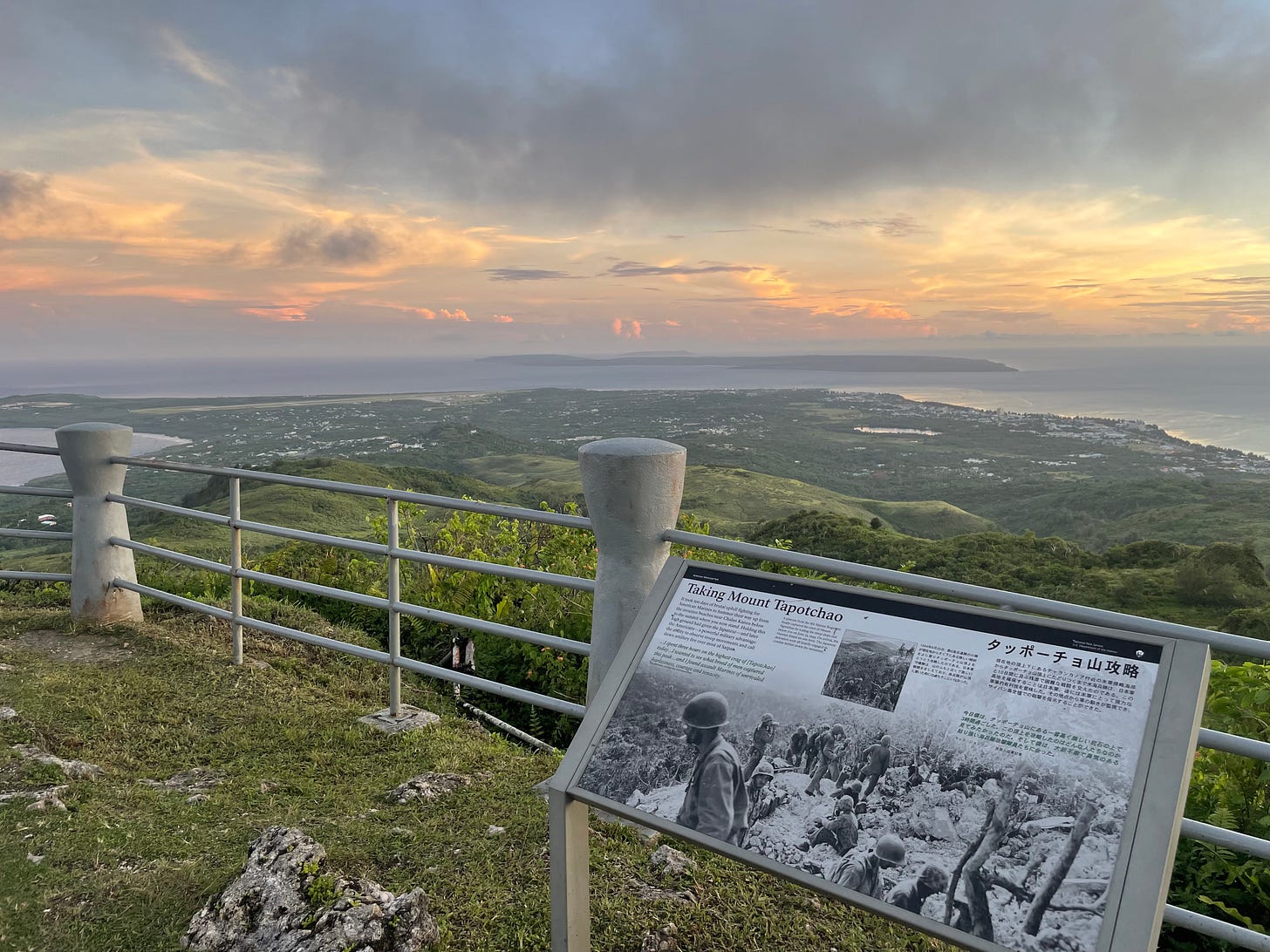

The caption for the plaque commemorating the capture of the summit:

TAKING MOUNT TAPOTCHAU

It took ten days of brutal uphill fighting for American Marines to hammer their way up from the invasion beaches near Chalan Kanoa below to the summit where you now stand. Holding this high ground had given the Japanese — and later the Americans — a powerful military advantage: the ability to observe troop movements and call down artillery fire over most of Saipan.

“…I spent three hours on the highest crag of [Tapotchao] today…I wanted to see what breed of men captured this peak…and I found assault Marines of unrivaled fearlessness, courage and tenacity…2

-Mac Johnson, civilian war correspondent

I have been hiking through the jungle a lot. As far as jungles go, the one here is gentle. It does not actively want to kill you all of the time. It doesn’t take much to be disoriented and lost, but you also have the comfort of knowing that you are never far from one of the two or three main roads and that there are no man-eating critters or any sort of snake. But we always wear gloves and high socks, sweating through our gear no matter what. The biggest risk I have probably been while hiking was when I was stung or bit on the face by some sort of bug on Saturday and I bolted, running the risk of tripping or getting lost more than the actual bite. As we scramble up and down, I often think to myself how grateful I am that I am carrying plenty of food and water, can just stop any time I want, and - most importantly - am not being shot at. And it is still quite tough.

There are many incredible anecdotes in Hallas’s book about the battle, but one in particular is of a thing that - thankfully - did not happen. D-Day in Normandy had only been nine days before D-Day in Saipan.3 In France, the 82nd Airborne, 101st Airborne, and British 6th Airborne parachuted behind in behind enemy lines to disrupt defenses and reinforcement lines in preparation for the beach assaults. The 1962 John Wayne movie The Longest Day and the second episode of the 2001 miniseries Band of Brothers “Day of Days” depict this component of the invasion.

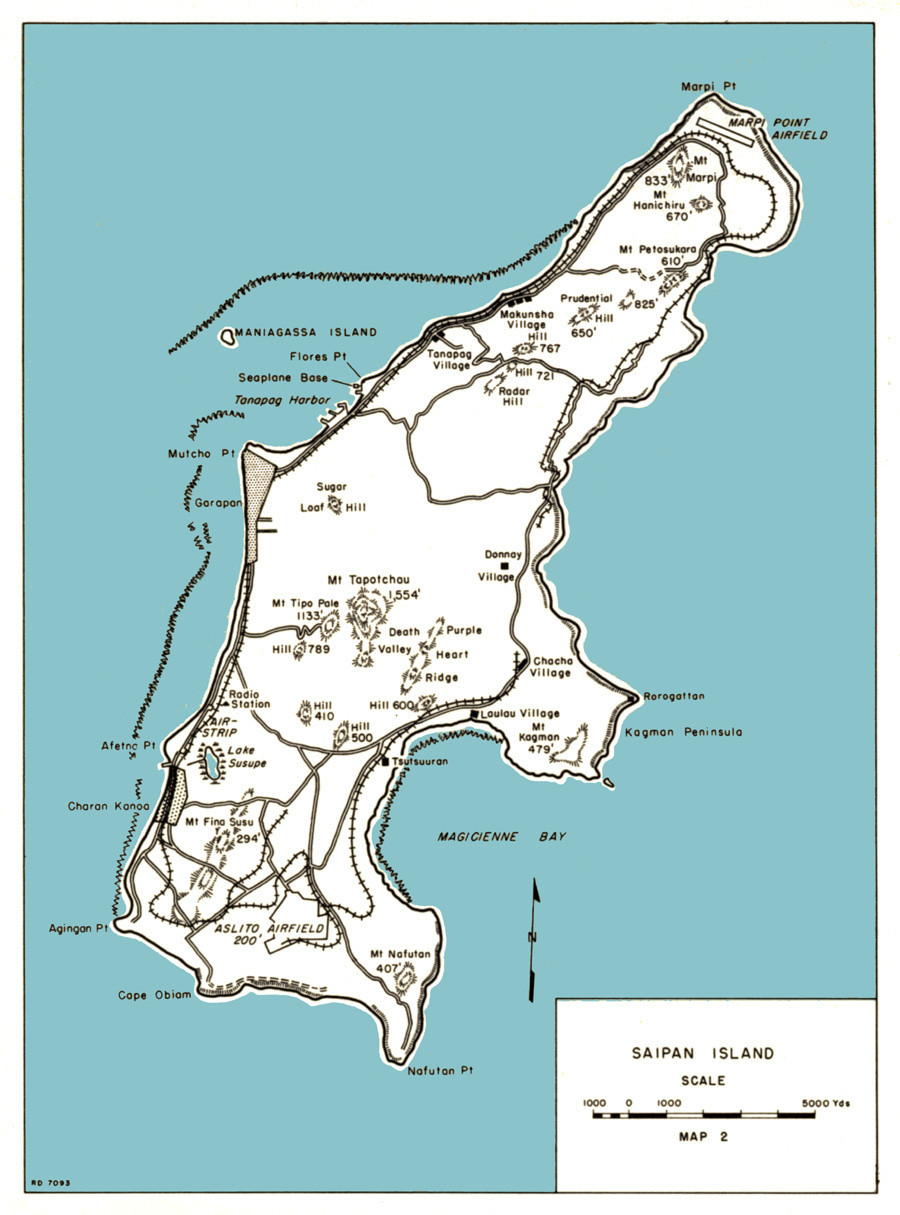

For the invasion of the island, there was also a plan for an advanced force to land on the night before the primary invasion to disrupt the defenses. It would have almost certainly ended in wholesale slaughter of the 1st Battalion, 2nd Marines. Though there was imperfect information about German fortification, the intelligence leading to the audacious airborne plan was substantially better than what the Saipan plan’s architect, Marine General Graves Erskine, was working off of for this operation. He proposed that the 200 men of Company A of the VAC Amphibious Reconnaissance Battallion4 would be towed in on rubber boats until they were 50 yards from the beach in Lau Lau Bay5

Under cover of dark and in silence, the VAC would secure a beachhead to allow for the 2000 men of the 1st Battalion, 2nd Marines to land an hour later. Then, without any heavy weaponry to preserve speed, they would bolt 3 miles up the summit of Tapochau. Once they secured the top, the heavier guns would be parachuted in and the Battalion would attempt to hold the high ground while the actual invasion occurred along the western beaches in the lagoon.

As the plan was passed down, the protests got increasingly loud. These Marines had handled the prior island-hopping missions and knew what was being asked based on scanty information. The VAC group was told that after landing and allowing the Battalion to move forward, they would take up the rear and would probably have to fight off “the enraged hordes of Japanese” in pursuit. One PFC was more blunt: “It sounded like pure suicide to me.”

Hallas’s understatment of the plan is that it “reflected a gross underestimation of Saipan’s rugged central terrain and the strength of Japanese defenses at Magicienne Bay.” Fortunately, one of the staff officers, Lt. COl. Thomas J. Colley, returned to where these operations were being cooked up at Pearl Harbor to point out in the “somewhat fuzzy” aerial photographs that there were defensive fortifications under construction. These photographs were taken from an aerial surveillance mission on May 29th. With extensive anti-aircraft guns and the desire to still be sneaky about where they would land next, the planes had to be much higher up. And, unlike the lowlying coral atolls, the canopy and cliffs meant that many of the fortifications would not show up from aerial photographs regardless.

Colley and his team made the case that it would “completely fail” that “those who might successfully be landed would be wiped out before getting very far toward their objective” and “the idea of this battalion successfully reaching the summit of Mt. Tapotchau before daylight, even from the viewpoint of terrain along, seemed incredible.”

Fortunately, the planned was abandoned. Marine Corps monograph summed up the lesson of finally abandoning the plan for being too likely to fail catastrophically with the observation that “the exact point where gamble becomes foolhardy venture is sometimes difficult to determine.”

After taking Tapotchau and proceeding down the far side, they captured the beach from the South and West, instead of through horseshoe kill zone. They found, under camoflauge that had shielded detection from the aerial photographs Erskine had worked off of, that “the beaches were backed by an extensive trench system, barbed wire, artificial obstacles, blockhouses, well-sited 120mm guns, and two 20mm mortars.” In understatement years later: “it is extremely fortunate that at least someone realized that this was going to be a catastrophe if it went forward.”

Even the more cautious plan was costlier than expected. I will leave you with an assessment from one of the survivors who Hallas spoke with for his book:

“Mount Tapotchau was rough, damn rough,” observed PFC William Bilchak. “You had Japanese shooting and throwing grenades down on you while you’re climbing ropes… Our guys knocked out 30-32 caves. They said there were 300 or 400 of them. We’d go in groups of four — one BAR, one M1 (rifle), one flamethrower and me. You’d put the flamethrower on one side, and the BAR on the other. When the smoke and flame got to them, they’d start coming out. They didn’t have a chance…You sent out four [Mainres] and if they got killed, you sent out another four. You all got your turn to live. You all got your turn to die. You don’t blame anybody. That’s just the way it was.”

This Smithsonian-affiliated museum is located in Fredericksburg, Texas, a small day-trip town an hour outside of Austin. This is an odd place for it. Locals are quick to point out that it is there because Admiral Chester Nimitz was raised in the converted hotel that started off the collection. But this is more of a ‘how’ than a ‘why.’ As thankful as I am that the museum is located in a popular tourist destination with substantial traffic, this rationale would be the same as putting the Apollo museum in Neil Armstrong’s hometown of Wapakoneta, Ohio, instead of in Houston or Cape Canaveral.

I will not begrudge Mr. Johnson his omission of the serial comma - keystones are precious in war. But if such a blunder is due to the style manual of the National Park Service, someone needs to write a letter.

Both invasions were called D-Day; It is the generic name for the day of a planned operation that preparation and executing goals are pegged to. H-Hour marks the hour of the operation’s start. D-Day minus one means the day before the intitiaion of the assault, D-Day plus seven means a week after. Within a few months, however, the June 6th operation in France became synonymous with the term and it stopped being used in common parlance for other operations.

These guys are incredible - I will write a post about them later.

The place names used by the Allies were, in many cases, wrong. This bay was called by the soldiers ‘Magazine’ but is actually called Lau Lau bay.

Really enjoying these articles. Thanks Jim