Last week, I experienced the 4th of July on Saipan. The CNMI celebrated the day as the 77th Liberation Day festivities. There were no fireworks at the public festival1 but, as I watched a troupe of South Korean teenagers with trombones blast out a rendition of the main theme from Star Wars with my new friends — a Chinese scuba-diver and a bagpipe-playing merchant marine from Pennsylvania — before a troupe of micronesian dancers took the stage, I realized that there was no better way to celebrate the American project.

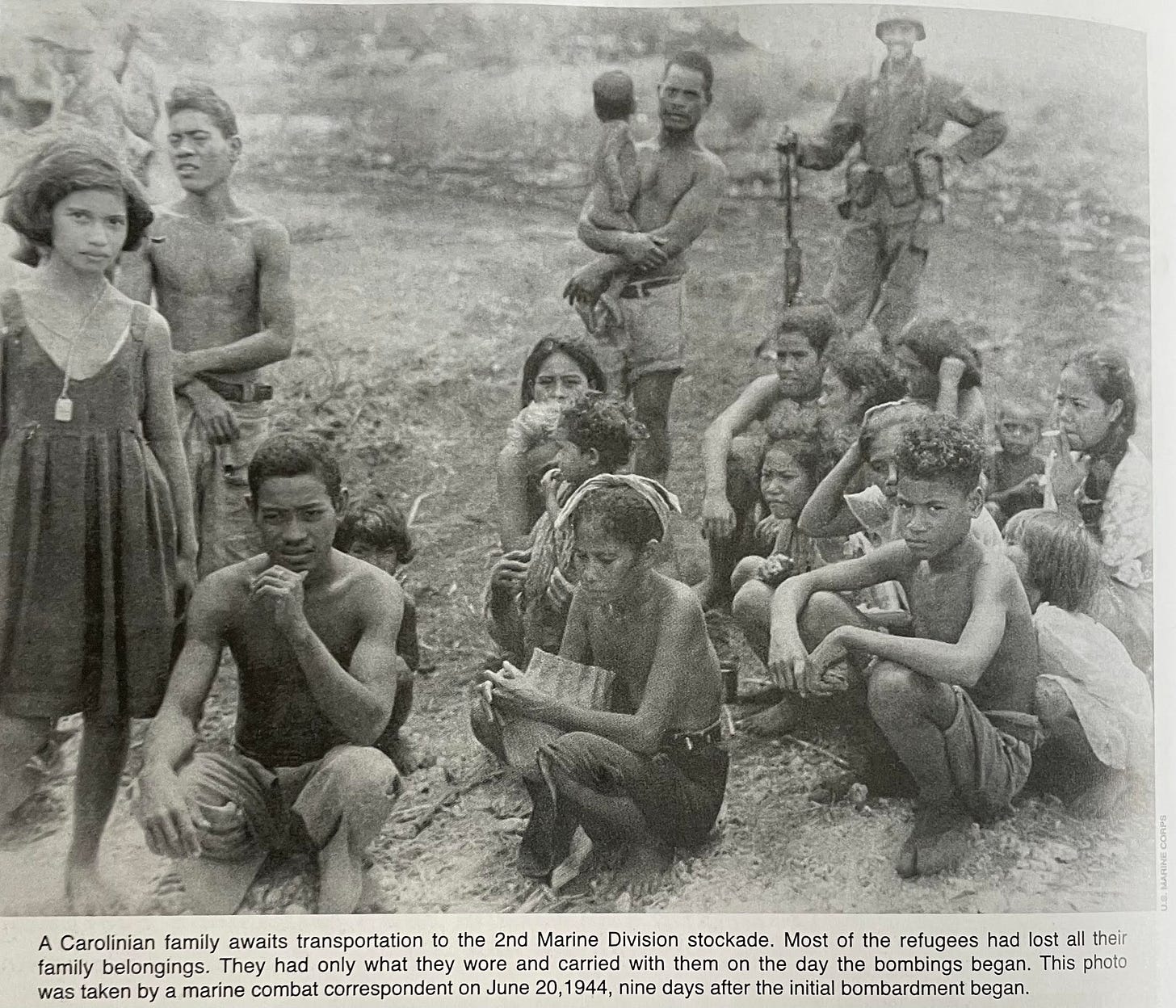

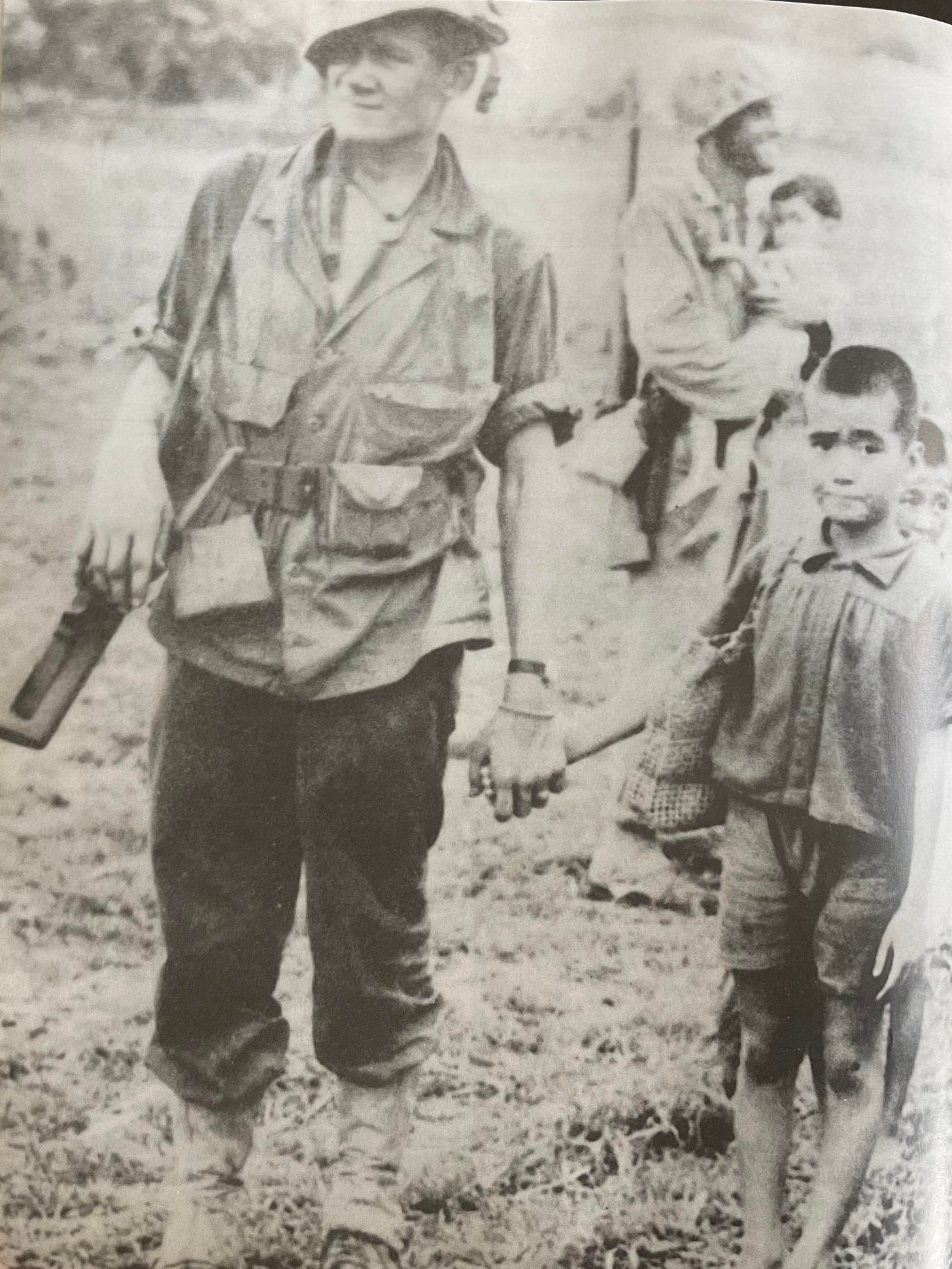

“Small numbers of civilians, ‘homeless, starving, naked, wounded, and in most cases terror-stricken by the savage fighting taking place but a few hundred yards away, suddenly appeared and clamored for assistance... There was little the Marines could do other than offer them a sip of water, while ducking incoming fire and tending to their own wounded comrades. With only the clothes on their backs, and some of them not even that, the refugees from the battle of Saipan huddled on the beach with their children for a long, cold and frightful night.”

Within a day of the landing, there were a thousand civilians on the landing beach. Saipan was the first place taken by the Allies with a substantial civilian population. As I have written about before, there had been a substantial agricultural operation focused on sugarcane production in the Northern Marianas since the 1920s. Chamorro and Carolinian locals, as well as home-island Japanese, were employed in the fields and refineries. Eventually Koreans - transported there from their occupied peninsula - and Okinawans2 were brought to the island.

During the 1930s, as Japan geared up for war, they instilled a racial hierarchy that mirrored some of the tenets of the state-sponsored Shinto beliefs that undergirded much of the war ethics of the soldiers. These status and race categories also made the nature of their surrenders to the Allies worse.

I will write extensively about the tragedies of Suicide and Banzai cliffs, where hundreds of civilians - believing that the Americans would do terrible things to them if captured - leapt to their deaths. But, unknown to these unfortunates, for three weeks at the southern end of the island, the Americans were struggling to figure out what to do with the civilians.

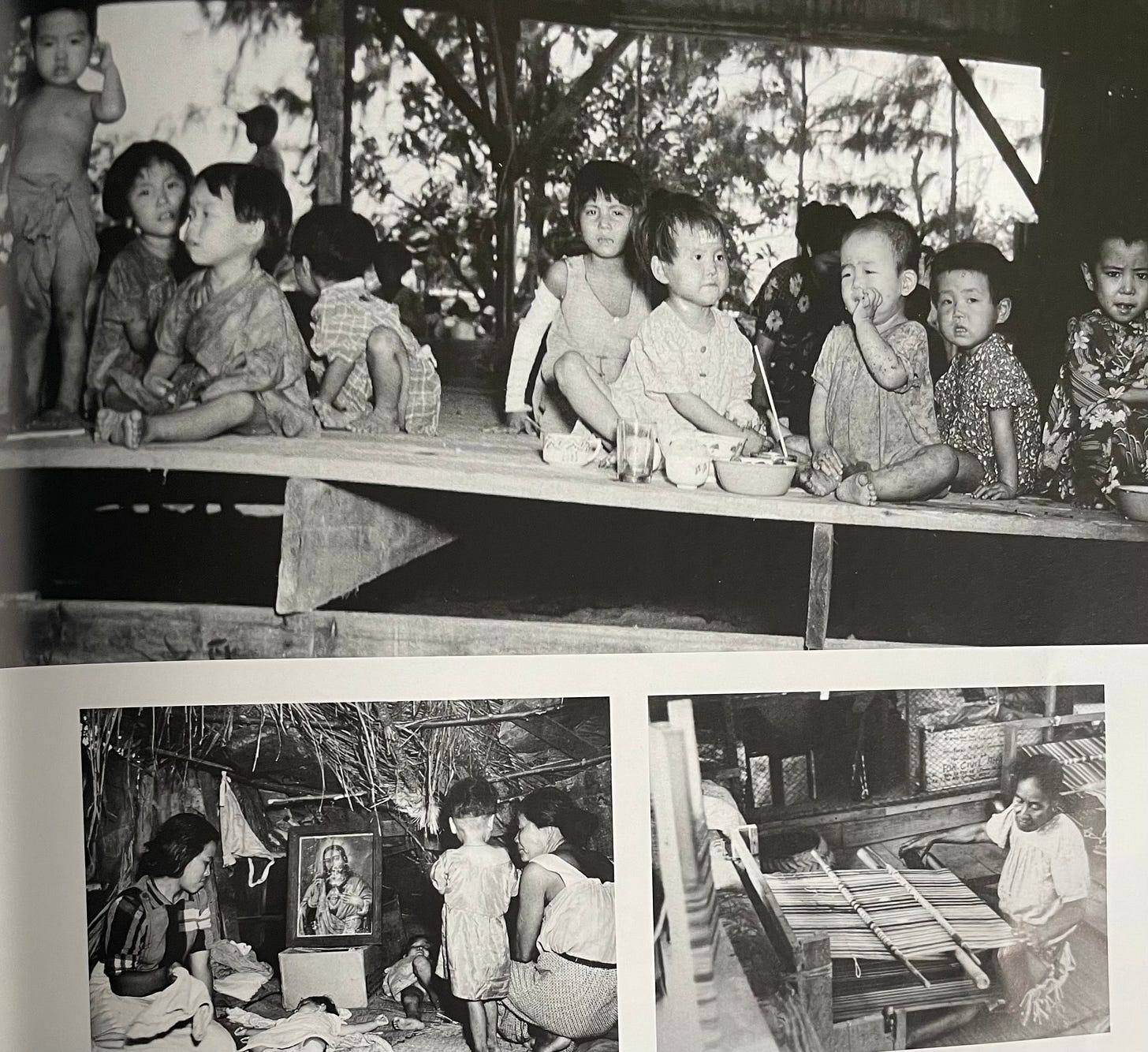

The ultimate answer was internment camps. These were fundamentally different than the mainland Japanese internment camps where American citizens and legal residents were lumped together because of their ethnicities and a racialized overreaction to legitimate national security concerns.

The initial camp was in Susupe, but ultimately a larger camp was built in Chana Kanoa, where much of the sugar refining had taken place.

On July 4, 1946, the final restrictions to entering and leaving the camps were lifted by the Naval government. This has been celebrated ever since as ‘Liberation Day,’ reflecting both the liberation from the Japanese and from the internment camp. By the time the CNMI joined the United States in the 1970s, they had been celebrating July 4th for decades.

Below are some of the photographs gleaned from The Marianas Variety and the Saipan Tribune, with my commentary in the captions.

There normally would be. The dire fiscal situation is part of why I am here.

In all of the writing and conversations here, ‘Okinawans’ are referred to separately than ‘Japanese,’ which reflects some internal cultural and ethnic distinctions of which I was oblivious.