Banzai - The most destructive banzai charge in history

D-Day + 22-22 - Battle of Saipan- July 6-7, 1944

The Battle of Saipan's strategic significance for bringing the Japanese home islands into range and its likelihood of provoking a decisive carrier battle were known before D-Day. But three things define the battle as fought: the firing of Army General Smith by Marine General Smith, the tragedy of Suicide Cliff, and the largest banzai charge in history. The third occurred 80 years ago today.

The best way to tell the story of that night is through the four servicemen who were awarded posthumous Medals of Honor from their actions during the Gyokusai.

PFC Harold Agerholm was from Racine, Wisconsin. He was a Marine artilleryman in the 4th Batallion, dug in to the southeast of a gulch that was called "Paradise Valley" by the Americans now, "Hara Kiri Gulch" by them then, and "The Valley of Hell" by the Japanese defenders.

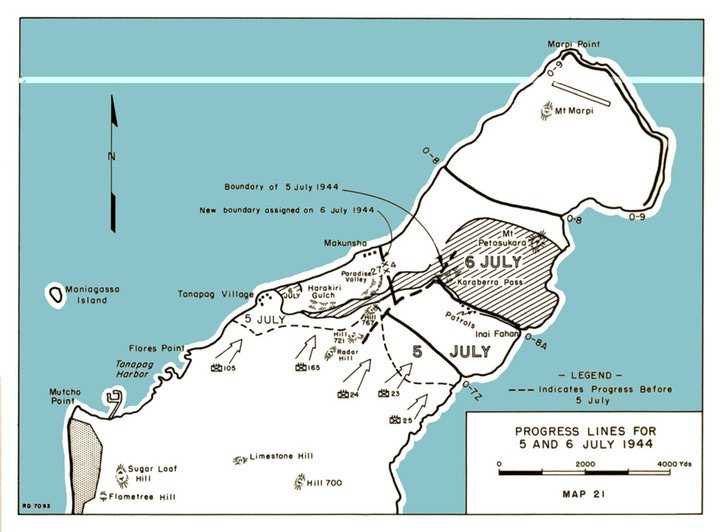

From many high points of Saipan, you can see the entire island. When these places were taken, they could often see battles developing far beyond when they could directly support, which some compared to watching field movements during earlier, Napoleonic times. Agerholm was on one of these heights, able to see the entire line of the Army's 27th infantry set just north of Tanapag. When your side won, it was an impressive sight. When the tables turned, you could only watch in horror.

What Agerholm observed was the carrying out of the last order of General Saito:

"I am addressing the officers and men of the Imperial Army on Saipan. For more than twenty days since the American Devils attacked, the officers, men and civilian employee of the Imperial Army and Navy have fought well and bravely. Everywhere they have demonstrated the honor and glory of the Imperial forces. I expected that every man would do his duty.

“Heaven has not given us an opportunity. We have not been able to utilize fully the terrain. We have fought in unison up to the present time but now we have no materials with which to fight and our artillery for attack has been completely destroyed. Our comrades have fallen one after another. Despite the bitterness of defeat we pledge 'seven lives to repay our country.'

“The barbaous attack of the enemy is being continued. Even though the enemy has occupied only a corner of Saipan, we are dying without avail under the violent shelling and bombing. Whether we attack or whether we stay where we are, there is only death. However, in death there is life. We must utilize this opportunity to exalt true Japanese manhood.

I will advance with those who remain to deliver still another blow to the American Devils and leave my bones on Saipan as a bulwark of the Pacific. As it says in Semjinkum [a volume of Battle Ethics], 'I will never suffer the disgrace of being taken alive' and 'I will offer up the courage of my soul and calmly rejoice in living by the eternal principle'Here I pray for you for the eternal life of the Emperor and the welfare of the country and I advance to seek out the enemy.

Follow me!"

He is not the first leader to claim that that he would be with them in a futile assault when he did not actually have any intention to do so.

After issuing the order, he had a farewell meal of crabmeat and sake and, along with his chief of staff and Admiral Chuichi Nagumo - the architect and 'hero' of Pearl Harbor who by happenstance was on Saipan - ritually committed hara-kiri, or seppukku. He slashed his belly with his sword, and then his adjutant shot him in the head.

The 1st and 2nd Battallions of the 105th Infantry Regiment of the Army, who had been the subject of the Smith squabble and had already been deeply bloodied at Naftan and Tapotchau, had the brutal assignment of taking the left of the line, the equivalent of the 2nd Marines who had to face the brunt of the Japanese counterattacks three weeks before as the the remaineder of the NTLF pivoted around them.

Every Japanese soldier capable of walking assembled with any weaponry they had remaining, sometimes mere sharpened sticks. Those that were too injured to walk gathered in groups around a grenade and committed suicide. There were approximately 5,000. Calls for reserves by the 105th went unanswered - as they had at Nafutan and Tapotchau. The gyokusai engaged the thin perimter north of Tanapag at around 0445 on the morning of July 7th.

PFC Agerholm watched in horror as the two batallions of the 105th and the 10th Marine Artillery Battery were overrun. Some wounded made it back to lines for treatment, but it was apparent what was going on. Agerholm "obtained permission" (official documentation seems to protest too much on this point) to take over an abandoned hospital jeep. He began to encounter wounded men. Loading in as many wounded onto the jeep as he could, Agerholm drove them to safety, dodging the banzai chargers.

Then he went back. Again. And again. In a Forrest-Gumpian effort, he single-handedly saved at least forty-five men that morning over three hours. A tactic from Purple Heart Ridge that killed many men finally got him. Two wounded men had been left in the open. When he ran out to assist them, a Japanese sniper shot and killed him. Harold Agerholm was 19 years old. His parents later recalled his penchant as a boy for bringing home stray and wounded animals.

"Gyokusai" means 'Shattered jewel.' It is a metaphor for an honorable death. A banzai charge is one of the methods that the bushido and state-shinto doctrines had prescribed for its soldiers, as were seppuku and kamikaze. There had been last stand charges before, just as it appeared morale was flagging, and there was an expectation of something of this type. But nothing prepared the US forces for the scope and scale of the charge here.

Survivor Lt. George O'Donnell, G Company, 2nd, 105th said that the Japanese were "like a crowd moving after a big football game, with everyone trying to get out at once."

B Company lost 21 men, including Sgt Barney Stoperas entire 8-man squad. They had run out of ammunition and fought hand-to-hand when they were overrun. The entire squad was found together, surrounded by thirty dead Japanese.

The Battle of Saipan is one driven by the Marines. But the banzai charge was about the Army.Thomas A. Baker was a boiler tender at the YMCA in Troy, New York, where he had grown up. He joined the Army before war had broken out. Over the two weeks before he was killed, Baker had distinguished himself as a "seemingly fearless combat soldier."

On June 19th, at Nafutan, his actions went against the bleak perception of the Army's will to fight that led Marine General Smith to relieve successive Army commanders.Baker had walked into an open field under heavy fire, shouldered a bazooka, and unloaded a shot at a Japanese dual-purpose gun. Then he fired it again, taking it out.On July 3rd, he volunteered for mopping-up duty near Tanapag. In an hour, he killed 18, including walking into and clearing a four-man pillbox by himself.

On the morning of the 7th, Baker's foot was blown off by artillery. As he kept crawling to get more ammunition to continue fighting, he was picked up first by PFC Zielinski, who was shot out from underneath him, then Capt Bernie Toft, also shot from unerneath him. When a third GI came to help him, he said "I've caused enough trouble already. I'll stay here and take my chances." He asked to be propped up against a pole and called out to a passing sergeant, Carlos Patricelli, for any weapon. Sgt Patricelli had recovered a .45. He checked that it's 7-round magazine was fully loaded with one in the chamber, lit a cigarette for Baker and put it in one hand, with the pistol in the other. According to Patricelli, "He was cool as a cucumber."

Two days later, Patricelli was sent forward to identify the dead. He found Baker propped up against the pole, a burned down cigarette in one hand, and the .45 in the other.

In front of him were eight dead Japanese.

It is hard not to recognize a dramatic difference in the style of leadership on the day of the Banzai charge between the American and Japanese militaries. After saying that he would be leading the charge that he was ordering, Gen. Saito killed himself. Lt. Col William O'Brien, on the other hand, was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his efforts to keep his Batallion together as it was being overrun.

Like Sgt. Baker, Col. O'Brien was also from Troy, New York. A Southpaw, he wore his shoulder holster under his right armpit. He had also picked up another .45. Survivors remember him stalking from position to position with his radioman, a pistol in each hand, alternating between calling in positions and commands through the radio and telling the GIs nearby "Don't give them a damn inch."He ordered the walking wounded to establish another line 100 yards to the rear and stayed behind.

Survivors saw him jump into a foxhole, retrieve a rifle from a wounded man unable to walk and empty it into the approaching horde. Then he crossed to a disabled jeep with a .50 caliber mounted on the reat.From his Medal of Honor citation: "When last seen alive he was standing upright firing into the Japanese hordes that were enveloping him. Sometime later his body was found surrounded by enemy he had killed."

I am going to make a full post about Capt. Ben L. Salomon, the other Medal of Honor recipient soon. The story of why he was not awarded the Medal until 2002 is the type of story that I like researching and telling. But no story of the July 7, 1944, should be told without acknowledging him.Benjamin Salomon was a dentist. They tried as hard as they could to make him stay a dentist. But on the morning of the July 7, he was acting batallion surgeon.

Capt. Salomon is one of the nine Eagle Scouts who have received the Medal. He is one of three dental officers who have, the other two being Naval officers in WWI. He is also one of three Jewish Americans to earn the Medal for World War II. He graduated from USC Dental School in 1937 and had a private dental practice. He was drafted in 1940 as an infantry private. He qualified as an expert in pistol and rifle and apparently did nothing to notify them that he was in fact a dentist. Salomon was a sergeant in a machine gun section two years later when the Army two years realized that they already had someone they "shanghai" into the Dental Corps. At first, he attempted to remain in the infantry and his commanding officer requested that he be commissioned a second lieutenant of infantry. The Army denied this request. He became a first lieutenant to serve in a hospital in Hawaii.

During his time there, he kept all of the same training regimen as the infantry. In 1943, he was promoted to Captain and assigned to the 105th and sent to work on one of the hospital ships to support the NTLF. On June 27th, the 2nd Batallion surgeon was wounded by mortar fire. Salomon volunteered to replace him. He came ashore and worked to treat the constant stream of wounded. On June 6th, he had positioned his medical tent about 50 yards behind the front line near Tanapag.

What happened next is surprisingly well-documented, given the chaos of the time. The efforts to by the men he saved to get Cpt. Salomon the Medal required a lot of testimony parsing of his exact actions.

Within minutes of the Banzai charge, there were two dozen wounded crowded into the tent. A Japanese soldier charged into the tent and bayoneted a wounded GI. Salomon grabbed a rifle and shot him, then clubbed two others as they charged in.

Four more Japanese came in from under the tent walls. He kicked a knife out of one mans hand, shot another, bayoneted a third, and drove the rifle butt into the stomach of the fourth, stunning him long enough for one of the wounded GIs could shoot him.

Then Salomon looked outside to see that the area was overrun with Japanese and it had devolved to hand-to-hand fighting around the medical tent. Knowing the wounded would be massacred, he ordered the walking wounded to try and escape to the rear. Then he set about trying to provide as much cover for whatever of his patients and comrades-in-arms that he could.

He then picked up a rifle and ran outside the doors of his tent, the expert marksman kneeling and squeezing off shots. Four GIs manning a nearby machine gun were killed in sequence, so he ran over, settled in behind the machine gun, and was firing away when he was last seen.His body was found behind the machine gun. He had repositioned it at least four times as the bodies piled up. He had seventy-six bullet wounds and at least 24 bayonet wounds he had received when alive.

The aftermath of the Banzai charge is difficult to comprehend. The 1st and 2nd Batallions had been "virtually wiped out." Of the 1200 soldiers dug in from those two batallions, 406 were dead and 512 wounded.The number of Japanese dead involved in the area of the charge, including suicides, was 3,190, but it is impossible to know exactly how many.It was one of the most devastating single battles of the entire war, 80 years ago today.